We hit the trail to learn what it takes to move cattle across Wyoming’s grizzly country

You can talk to Wyoming rancher Charles Price all day about the fine points of raising cattle, or maybe two days. With his down-to-earth manner, you’d probably never guess that you’re also talking to a PhD in nuclear engineering who formerly worked on some of the most advanced energy technologies in the world.

But that’s generally the way ranchers are, contrary to the swaggering Hollywood caricature. They’re plainspoken, polite, reticent almost to a fault. Most betray little of the remarkable skill and tenacity it takes to live this life, and to keep a ranch going that’s been in the family for four, five, or even six generations. Price could brief you on the pros and cons of nuclear breeder reactors. But he much prefers to talk about his real passion—breeding and raising some of the world’s finest beef in Wyoming’s Upper Green River Valley.

Raising livestock in this majestic but rugged landscape, where mountain men and American Indians held raucous rendezvous in the 1840s, may not be nuclear science. But it isn’t as simple as it may seem to urban dwellers and coastal elites, whose working knowledge of beef starts and ends at a McDonald’s drive thru. Hundreds of miles away, on the urban end of the supply chain, beef comes neatly wrapped and packaged in paper or cellophane, often between a bun, complete with all the fixings. But it originates here, in rural Wyoming, where Price and other local ranchers are trying desperately to keep their traditions, and traditional ways of feeding the world, alive.

I was there in June with MSLF colleagues to see the famed Upper Green River Drift, believed to be America’s oldest and longest-running cattle drive. It didn’t disappoint. There it was, like something out of the movies—a mooing mass of cattle plodding along, with whistling cowboys and tireless cattle dogs in pursuit. But it’s not a movie set. It’s not a historic reenactment. It’s the real deal, an honest-to-goodness, good old-fashioned cattle drive, still alive and kicking up dust in the 21st century American West.

Our journey began on a six-lane Denver freeway, and we reached our borrowed cabin, high in the Wind Rivers, at the end of a rough dirt road. The mountain cabin was spectacular in a rustic, rough-hewn sort of way, with massive timbers that the owners themselves harvested, milled, and assembled, Lincoln log-style. The requisite moose head was there, too, sternly glaring down on us. Cell service was impossible to find, even if we walked to the edge of a clearing and frantically waived our phones above our heads. At an elevation of 9,000 feet it gets cold, even in June. The cabin’s heating came from a monster wood stove that looked like an old tugboat boiler. Some kind soul had stuffed the stove to the gunnels with split wood, sparring us some initial hard labor. And it roared to life with the help of an explosive concoction called “diesel sawdust,” which I wouldn’t recommend for use at home.

Severed from civilization as we were, and with no gadgets to comfort us, we turned to other forms of entertainment, like watching lawyers split wood. And two broken ax handles later, they really seemed to be getting the hang of it.

We rose the next morning to the dark and the cold, because the stove had gone out. And we counted our blessings for indoor plumbing. We used another luxury item, the 1980s-era microwave, to heat dark black coffee, just like the real cowboys drink, before piling groggily into the SUV for our winding and rutted ride down to the rendezvous point. The first of many eye-openers for us was the brutally long hours these cowfolk keep, with workdays that begin and end with the sun below the horizon. The day required a 4 a.m. reveille in order to reach a 5:30 am rendezvous with Price at the “end of the oil” (meaning the end of paved road), where the Bridger-Teton National Forest begins.

The skies were somewhat brighter, but the sun still wasn’t up, when we met Price. Even in the morning half-light it’s hard not to notice a brown sign, emblazoned with a massive grizzly paw, warning all who pass there to be “bear aware.” This is grizzly country, lest anyone forget.

Tagging along with Price and fellow ranchers in the Green River Cattle Association offers a crash course in seeing things through a rancher’s watchful eyes. Where I see only a mooing mass of burgers and steaks, he sees calves who’ve been separated from the heifers, or vice versa. He sees when an animal is physically sound, or not. He scans the tree lines for stragglers. He cautions his guests against sudden moves that would spook the herd. These cattle can tolerate trucks, dogs, and horses; but not so much, gawkers from the city with loud voices, video cameras and whirring drones.

It quickly became apparent to this “city slicker” that ranching isn’t one skill but many. Today’s rancher also must be part-time mechanic, veterinarian, geneticist, weather forecaster, botanist, chemist, and technologist. Generations of sustainable ranching prove their credentials as excellent naturalists and conservationists. To succeed in the business of ranching, he or she must also stay tuned to global and national trends in the agricultural market.

It also takes a master logistician to pull off a cattle drive of this scale. Involved are roughly 6,000 cattle, belonging to a dozen different families or “outfits,” some of whom have been doing this annually since the 1890s. Cattle must be nudged, prodded, and cajoled up to 80 miles. It’s a long but gradual march, done in phases, usually in the cool of the morning. Driving the animals too far in the heat of the day would harm them. The herds and their mounted handlers cross a patchwork of public and private lands, using a network of overpasses, bridges, trails, and roads, paved and primitive. Some outfits are moving cattle for 12 to 14 days, depending on conditions. Those traveling the farthest can spend nearly a month on The Drift, before the livestock reach the summer allotments.

There the animals will be watched through the summer months by range riders, who keep predators at bay, as best they can, and move them from pasture to pasture to avoid overgrazing. When summer turns to fall, the process is reversed, as cattle “drift” back to lower elevations, instinctively prodded by the oncoming winter. There they are gathered, counted, sorted, and in some cases shipped to market.

Sadly, today’s ranchers also need to have familiarity with laws and courts, given how frequently public lands disputes and other matters of life or death to a cattle outfit can end in litigation. That’s what brought MSLF lawyers and our rancher-clients together on this June weekend—a court case, which could impact the fate not just of these ranchers, but of all ranchers who rely on public lands grazing.

The case, Center for Biological Diversity v. Bernhadt, could determine whether ranchers and federally protected grizzly bears can continue to coexist on the federal grazing allotments where these herds are headed. At issue is whether documented problem bears can be removed by the state of Wyoming, when repeated cases of predation occur, as has been the accepted practice since the 1970s. Otherwise these lands will essentially become a grizzly bear buffet, where open season is declared on domestic livestock and ranchers can figuratively and literally be eaten out of house and homestead.

The balance between profit and loss, survival or financial ruin, has always been precarious for ranchers. But the growing toll grizzlies and wolves are taking on these ranchers, and the determined efforts of organized antigrazing groups to use grizzly protection as a pretext for running them off their federal allotments, is pushing some families to the brink. This at a time when they confront a host of COVID-19-related supply chain challenges.

The State of Wyoming compensates ranchers for these losses, when the kills can be documented and confirmed. That isn’t always easy, however, given the vastness, ruggedness, and remoteness of the terrain. Documented problem bears currently can be removed by state officials. But such steps are taken reluctantly, and only under the care and expertise of wildlife officials.

Now anti-grazing groups, in a radical reversal from long accepted practice, are pushing to effectively ban the removal of problem bears. It would almost certainly make use of these allotments untenable—and that’s exactly what the antigrazing groups are aiming for.

Killings that used to be rare are today alarmingly common, accounting for 10-20% of the losses these ranchers suffer in a summer. And there’s little hope that those rising fatality figures will fall, as grizzly bear and wolf numbers continue to rise. Rather than recognize a fully recovered grizzly population as a conservation success story, environmental extremists have opposed the government’s repeated efforts to delist the species and hand more management responsibilities back to the states. These groups keep moving the goal posts, keeping their donor base alarmed by painting a ridiculously dire picture of realities on the mountain.

The extremists’ first run at a radical new “no take” rule prohibiting bear management came in the form of a preliminary injunction, aimed at suspending all lethal removals until the delisting debate is finally settled. MSLF successfully beat back that effort, when a federal judge agreed with us that continuing with current grizzly management practices, pending resolution of a related suit, posed no threat to the species.

The ranchers we met on The Drift are great lovers of the land and the wildlife. They just want to coexist peacefully with the grizzly bears. They want federal protections lifted, as required by law, in recognition that the grizzly bear population’s recovery goals have not just been met but exceeded. They want responsibility for managing the animals returned to the states, so they can continue to use their summer pastures without losing so many animals to wolves and grizzly bears that they go out of business. If the extremists win in court and open season is declared on domestic livestock, these pastures would likely no longer be suitable for grazing, which could strike a mortal blow to those ranching families and ranch workers who depend on the summer range to make their business work and to keep America fed.

Ranching in the American West can seem like a solidary endeavor, suited only to the “rugged individualists” of popular lore. But success here also depends on ties to family and community—a word that one continually hears, but rarely sees, in urban America. What many describe as an “industry” is, at this end of the supply chain, largely a family affair, often spanning six or seven generations. Outfits running The Drift often consist of extended family and neighbors working side by side. A time-honored tradition of mutual assistance spans the valley, with friends and associates gamely chipping-in and sharing burdens that might overwhelm any one family. It’s a tradition that also will be lost if The Drift goes way. MSLF doesn’t intend to let that happen. Like rangers riding to the rescue in an old western, our attorneys are fighting for justice on behalf of these ranching families.

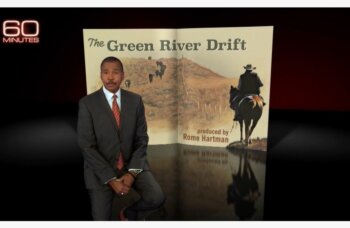

Watch the short video below, taken during our trip to visit ranchers on the cattle drive.